What Happened When Switzerland Got Serious

An Oxford study maps how $88.6 billion in annual African capital flight pivoted from Western havens to Dubai, Singapore, and Hong Kong after post-2008 regulatory tightening. Tracing where the money went requires the kind of curated, in-language source knowledge that no sanctions database can replicate.

Every year, an estimated $88.6 billion in illicit capital leaves Africa. That figure — drawn from a 2020 UNCTAD study of 2013-2015 averages — exceeds the $73.6 billion the continent received in official development assistance in 2023, the bulk of it from the US, Germany, France, Japan, and multilateral institutions like the World Bank. More wealth exits through hidden channels than enters through the front door of international aid.

Where does it go? An Oxford study published in early 2026 by Ricardo Soares de Oliveira — senior research fellow at the Oxford Martin Programme and professor at Sciences Po — maps the answer. When post-2008 regulatory tightening made traditional Western havens like Switzerland and the Channel Islands less hospitable, African capital flight pivoted. Dubai, Singapore, and Hong Kong became what de Oliveira calls among the fastest-growing and most significant transnational connections for Africa's offshore economy. The ICIJ reported on the findings in February.

The geographic shift is well documented. What's less understood is the screening gap it created. The tools most compliance teams rely on — platforms that aggregate international sanctions lists, PEP databases, and adverse media — were architected primarily around Western financial systems. These three Asian hubs operate in languages, registries, and regulatory environments those tools still struggle to penetrate at depth.

The Geographic Shift

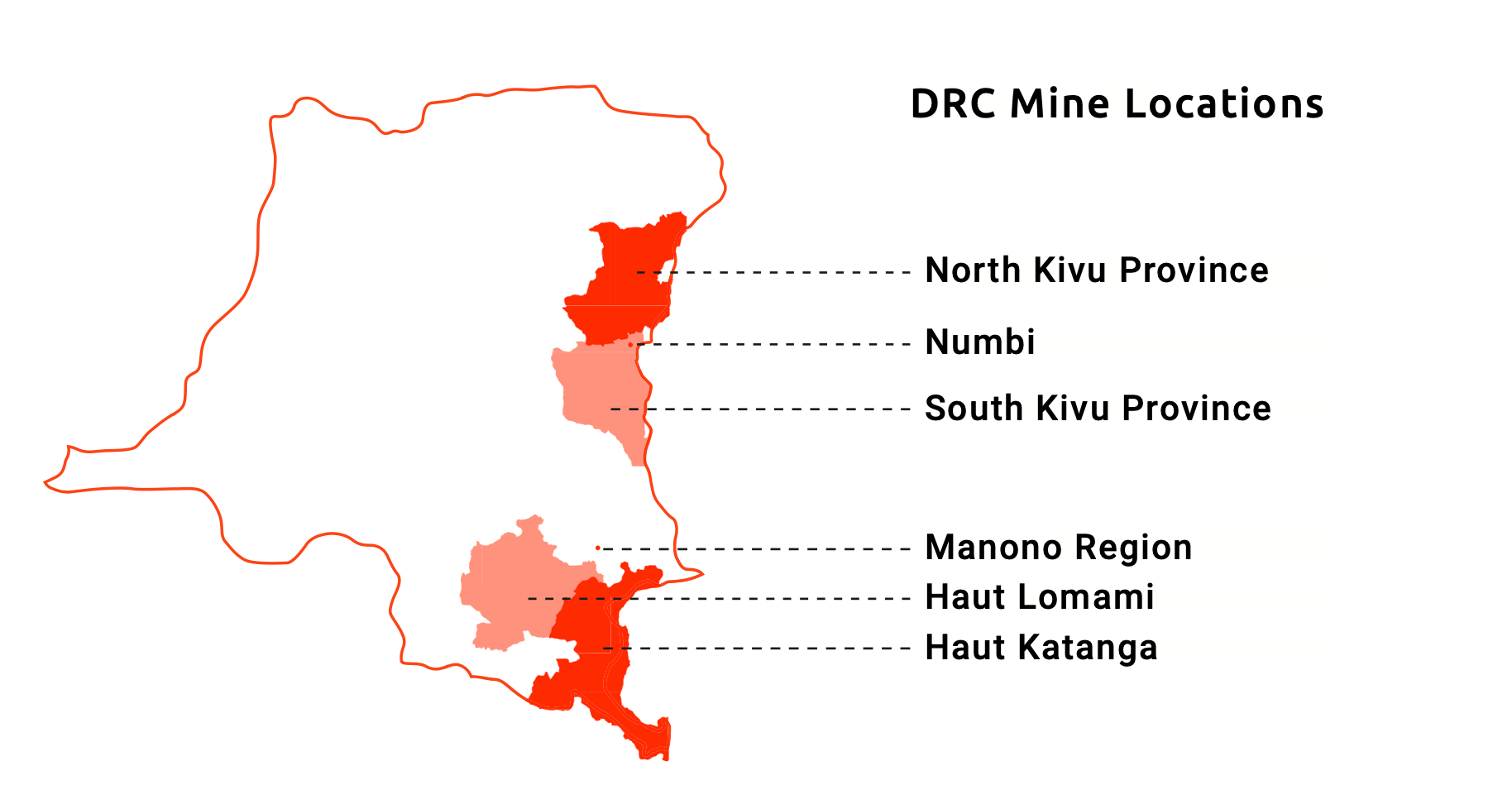

Dubai sits at the center of the study's findings. The UAE is now the fourth-largest source of foreign direct investment into Africa. According to de Oliveira's research, it handles roughly 95% of illegal gold originating from East and Central Africa. The UAE has become a landing zone for figures facing scrutiny elsewhere: Isabel dos Santos, once Africa's richest woman and now subject to Interpol red notices, and the Gupta brothers, wanted in South Africa for state capture. Evidencity has documented these gold pipelines in prior investigations — tracing conflict mineral flows from

eastern Congo through UAE-linked entities, and mapping how 97.5% of

Central African Republic gold production disappears into smuggling networks that terminate in Gulf trading houses.

To its credit, the UAE has moved aggressively since being placed on the FATF grey list in March 2022. It established a dedicated financial crimes court, expanded its Financial Intelligence Unit, launched the goAML suspicious activity reporting platform, and suspended 17 precious metal dealers in 2023 for failing to report suspicious transactions. FATF acknowledged the progress and removed the UAE from its grey list in February 2024. But reform and residual risk coexist — a point we'll return to.

Hong Kong, meanwhile, served as Mossack Fonseca's busiest global office, channeling 29% of the firm's active shell companies through its Hong Kong and China operations before the Panama Papers brought the edifice down in 2016. Singapore hosted two of the most prolific enablers exposed by successive leaks: Portcullis TrustNet, named in the 2013 Offshore Leaks, and Asiaciti Trust, fined S$1.8 million by the Monetary Authority of Singapore in 2020 for anti-money laundering failures spanning over a decade.

Three hubs. Three different regulatory architectures. Three different languages and corporate registry systems. And one common thread: each sits in a jurisdiction where the depth of local source material — court records, corporate filings, enforcement databases, independent media — demands more than automated screening against international watchlists.

What Screening Misses

Conventional compliance platforms are powerful at what they do. World-Check covers 240 countries and claims sources in 64 languages. Dow Jones Risk & Compliance draws from over 32,000 sources through Factiva in 28 languages. These tools will tell you whether a name appears on OFAC's sanctions list or an Interpol notice. They aggregate, they index, they score.

But aggregation is not investigation. Knowing that a source exists in a language is not the same as knowing what that source contains, how to access it, or where its blind spots are.

Take Singapore, where Portcullis TrustNet and Asiaciti Trust operated for years. Evidencity's Country Resource Library (CRL) for Singapore maps over 55 local sources — including Monetary Authority enforcement actions, the ACRA corporate registry, and the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Register, which requires a fee to access. The Singapore Police Force's published commercial crime prosecution records cover only 2014 to 2017. A platform scraping public databases wouldn't flag that limitation. A CRL does.

Hong Kong is more complex. The Companies Registry requires login via "Unregistered User" with a Hong Kong or foreign ID number. The Audit Commission requires physical retrieval of documents. And the media landscape carries its own intelligence: Ming Pao, one of Hong Kong's leading Chinese-language newspapers, fired its chief editor after the outlet ran Panama Papers coverage — a fact that tells an investigator something critical about the independence and reliability of local reporting in that jurisdiction.

This is what a CRL maps: not just sources, but access methods, language requirements, reliability ratings, and known gaps. Evidencity maintains CRLs for 50 core countries — including Singapore and Hong Kong — with quarterly updates on a total of 80. These CRLs are the foundation on which Illicit Network Intelligence is built. When a network spans from eastern Congo through Dubai to a shell company registered in Singapore, tracing it requires source-level knowledge in every jurisdiction along the chain.

The List You Follow Depends on Who Wrote It

The UAE's FATF delisting in February 2024 should have simplified matters for compliance teams. It didn't. Two months later, the European Parliament voted to

keep the UAE on the EU's own high-risk third-country list, citing concerns over Russian sanctions evasion and conflict-zone gold laundering. Transparency International EU pointed to what it called glaring deficiencies in real estate transparency and precious metals oversight. Middle East Eye, reporting on a Politico investigation, documented that representatives from Germany, Italy, Greece, and the United States had declined to challenge the UAE's accelerated removal from the FATF list — even as Belgium's representative to the International Co-operation Review Group raised objections.

The EU didn't align with FATF until July 2025 — a 17-month gap during which two of the world's most authoritative regulatory bodies disagreed on whether one of the world's largest financial hubs had earned a clean bill of health.

For corporate counsel, the implication is practical: when multilateral bodies themselves can't agree on jurisdictional risk, automated scoring that relies on their outputs inherits their contradictions. A screening platform that updates its risk model when FATF delists a country will show one result. A platform that weights EU designations will show another. Neither is wrong. Both are incomplete.

The only way to resolve that kind of uncertainty is locally contextualized and curated source knowledge: mapped access methods, reliability-rated media, jurisdiction-specific operational nuance. It’s not about which list says what. It’s about what the source landscape actually reveals. This is why big data is not enough for transparency.

Seeing Where the Money Went

The Oxford study's most important finding is that, as de Oliveira argues, reforms that aren't truly global simply shift business to more permissive jurisdictions. The same principle applies to screening: tools calibrated to Western financial architectures don't automatically extend to hubs with different languages, access requirements, and regulatory cultures.

Evidencity's Country Resource Libraries exist because these jurisdictions demand it — 50 core countries, quarterly updates across 80, reliability-rated sources, in-language coverage, vetted source networks. That curated, locally contextualized source knowledge is what enables Illicit Network Intelligence to trace networks across borders, from conflict zones to financial centers to shell company registries. When $88.6 billion in African capital flight migrates to hubs where conventional tools can't read the local landscape, the question isn't whether your screening is running. It's whether your screening can see.