Mining Slaves in Central African Republic Reveal a Billion dollar Smuggling Ring

A Chinese embassy warning has fingered what NGOs and media outlets have been reporting for years: a 60 billion gold smuggling network operates across Africa, and modern compliance frameworks are blind to it.

In November 2025, China's embassy in the Central African Republic (CAR) warned Chinese citizens seeking work in the country's gold fields that they risk becoming "mining slaves.” This warning points to a multi-billion dollar blind spot that facilitates forced labor at an industrial scale in global gold supply chains, one that has grown significantly as the price of gold has reached historic levels on global markets.

According to NGOs and media reports, the CAR produces between two and six tonnes of gold annually. Official records report approximately one tonne; this means that over 90% of the country's gold production is smuggled and unreported. It quietly crosses borders en route to Dubai's gold markets where it is mixed with legally mined gold, and enters global commerce with no traceable connection to its origin.

CAR accounts for less than 0.2% of global gold production, so its impact in broader global gold markets is very small. CAR’s story, however, reveals how illicit networks operate at scale, and why it’s so hard to detect and deter these illicit networks.

SwissAid's

May 2024 report documented that smuggled African gold represents approximately 13% of global production annually. At 2025 gold prices, that's 435-439 tonnes worth approximately $59-61 billion entering global markets through undocumented networks that operate in a similar fashion to those in CAR: armed group control, systematic document falsification, origin laundering through regional hubs, and Dubai as the mixing point that obfuscates sourcing.

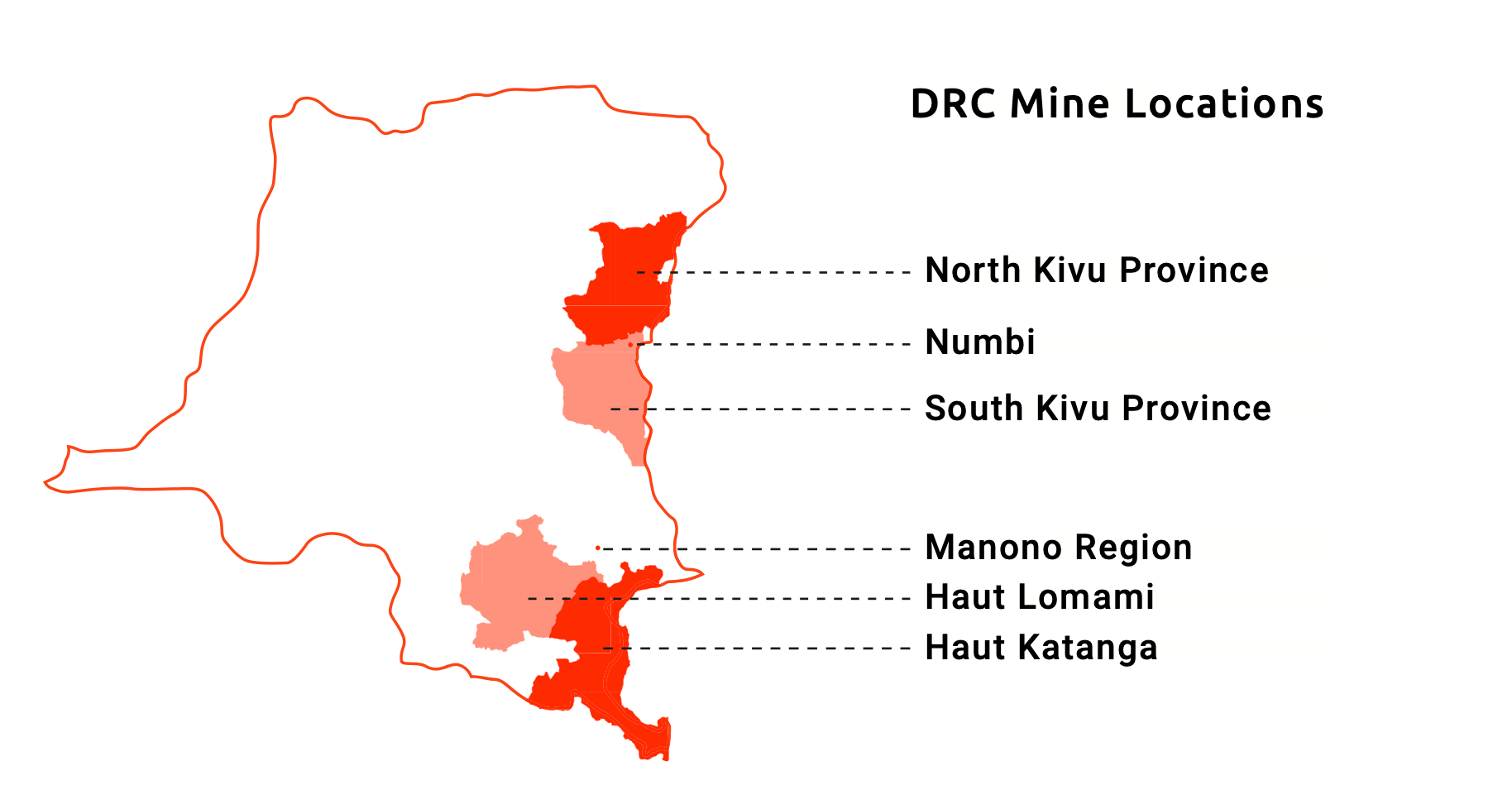

The pathways documented in CAR, such as the Garoua-Boulai to Cameroon smuggling route, false origin declarations at ports of entry, and Dubai refineries looking the other way, all point to one bottom line: survey-based compliance is not enough. This type of compliance is replicated across the DRC, Sudan, South Sudan, and Uganda. Different countries, identical architecture.

Multiple investigations have documented the smuggling routes. According to The

Sentry's 2023 analysis and

recent research on the Wagner Group by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, CAR gold moves West through Cameroon, or East through Chad, Sudan, and South Sudan. An estimated 95% of East and Central African gold eventually lands in Dubai.

The scale reveals systematic laundering.

SwissAid's November 2025 report documented the UAE importing 748 tonnes of gold from Africa in 2024—an 18% increase from the previous year. Uganda exported 31 tonnes to the UAE in 2024, up from 14 tonnes in 2023. Rwanda exported 19 tonnes, up from 13.8 tonnes. None of these countries have industrial mines or sufficient artisanal output to justify such export volumes. They serve as transit hubs for smuggled gold from neighboring countries, including CAR.

Behind CAR's mining sector sits the Wagner Group. The Russian paramilitary organization's Ndassima gold mine generates approximately $100 million annually, according to the Global Initiative's October 2025 investigation. Yet official documents show zero declared output and no recorded exports. Sources indicate the gold is smuggled abroad on covert flights through Somalia to Dubai. The London Bullion Exchange’s Responsible Sourcing

June 2025 newsletter explicitly mentioned Wagner operations in CAR. This is a rare public acknowledgment of malfeasance by the industry's leading authority.

Existing frameworks can't see illicit gold.

The London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) requires annual third-party audits of all Good Delivery List refiners, following OECD Due Diligence Guidance. Yet a 2023 EU assessment scored the program as only "partially aligned" due to uneven implementation by refiners and assurance providers – a gap serious enough that LBMA issued a rare public "Sourcing Advisory" on the UAE in 2024. New transparency requirements taking effect in January 2026 mandate public disclosure of refiner and exporter identities in "red flag" locations, including CAR, which is explicitly identified as conflict-affected and high-risk.

Again, a core structural problem is survey-based compliance.

Companies request Conflict Minerals Reporting Templates from suppliers. Suppliers self-report their sources. Refiners self-report their inputs. When gold is smuggled from CAR to Cameroon with false documentation, melted with other sources, and sold with "clean" origin papers, every survey in the chain shows compliant sourcing.

In the United States, Dodd-Frank Section 1502 covers gold from ten countries, including CAR. Publicly-traded companies must conduct origin inquiries and file annual reports with the SEC. After a 2017 court ruling, however, the SEC stopped requiring specific product labeling or independent audits. Companies can indefinitely report origins as "undeterminable" as long as they describe due diligence efforts.

The framework's weakness is measurable.

A

2024 Government Accountability Office (GAO) study found the SEC disclosure rule "has not reduced violence in DRC and has likely had no effect in adjoining countries." Violence has spread around informal gold mining sites. GAO noted gold is "more portable and less traceable than the other three minerals." The other three being tin, tungsten, and

tantalum.

Once gold is melted, the origin becomes undetectable via chain of custody documentation. Refining defeats traceability, unless forensic methods are used, which are not standardized across the supply chain because these methods are costly and time consuming. When 97.5% of a country's production enters commerce with false documentation, compliance frameworks fail.

They track documentation, not gold composition.

Standard due diligence was built for documented supply chains. It fails completely when facing CAR's reality: artisanal operations with no licenses, armed group control outside government authority, and systematic origin falsification at every border crossing.

This explains in part how 283 U.S. publicly-traded companies could list a Belgian refinery in their 2018 SEC filings after it had failed its Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI) audit and been removed from the approved list. It wasn't deception; it was systemic blindness. When companies admit they "lack sufficient information to determine origin," as Sony did in its 2017 filing, they're acknowledging a fundamental truth: survey-based compliance cannot detect smuggling networks built on document fraud.

The new LBMA transparency requirements taking effect January 2026 will force refiners to publicly disclose high-risk suppliers and locations. Companies downstream, toward the market, will face harder questions: not just "did you conduct due diligence?" but "can you demonstrate actual visibility into origins?"

When China's embassy warned about "mining slaves" in November 2025, it documented what compliance frameworks miss. This isn't a CAR problem requiring better governance. It's a visibility problem requiring different tools, and better data.

Evidencity's Illicit Network Intelligence data maps what conventional compliance cannot see: the relationships, entities, and pathways moving gold from mine to market. The networks operating in CAR operate regionally; their five tonnes reveals how a total of 439 tonnes or USD59 billion in annual value is functionally invisible to standard due diligence, exposing refineries, miners, and the banks that finance them to a multinational smuggling network that is invisible to standard screening practices.