How sanctions lists work and their limits

Sanctions lists are one of the most common tools in compliance and due diligence. They flag people, companies, vessels, and states that governments or international bodies restrict. Checking names against these lists is often the first step in risk screening. But relying on them alone creates blind spots.

What sanctions lists are

The main lists come from the US (OFAC), EU, UN, and UK. They aim to block sanctioned parties from finance, trade, or political legitimacy. A name on the list can mean frozen assets, travel bans, or trade restrictions.

How sanctions lists are compiled

Sanctions decisions are political and legal. Governments weigh intelligence, security concerns, and foreign policy goals before designating someone. Updates can be slow, and every jurisdiction applies its own criteria. This creates gaps — someone sanctioned in the US may still operate freely in Europe, and vice versa.

The limits

Sanctions lists have several weaknesses that make them unreliable as a sole control:

- Incomplete coverage: Many high-risk actors never appear. Sanctioning requires political will, evidence, and process. Not every bad actor meets those thresholds, meaning plenty of problematic individuals and companies stay “off the radar.”

- Timing delays: Names often appear after damage is already done. A company may have laundered money, supported armed groups, or supplied sanctioned regimes for years before it finally lands on a list.

- Political selectivity: Designations reflect political priorities as much as legal standards. Some actors escape sanctions due to strategic alliances, while others are added quickly to make a political statement.

- Jurisdiction gaps: Sanctions are not universal. Someone blocked by OFAC may operate in Asia or Africa without issue. The same vessel could be sanctioned in one region but continue moving goods elsewhere under a different flag.

- False sense of security: Lists can be used as a box-ticking tool. If compliance stops at “no match found,” organizations risk missing deeper ties, shell structures, or front companies set up to bypass sanctions.

Pre-sanction screening

Because of these weaknesses, due diligence cannot rely only on official lists. Pre-sanction screening is about identifying risks before they become official designations.

How it works:

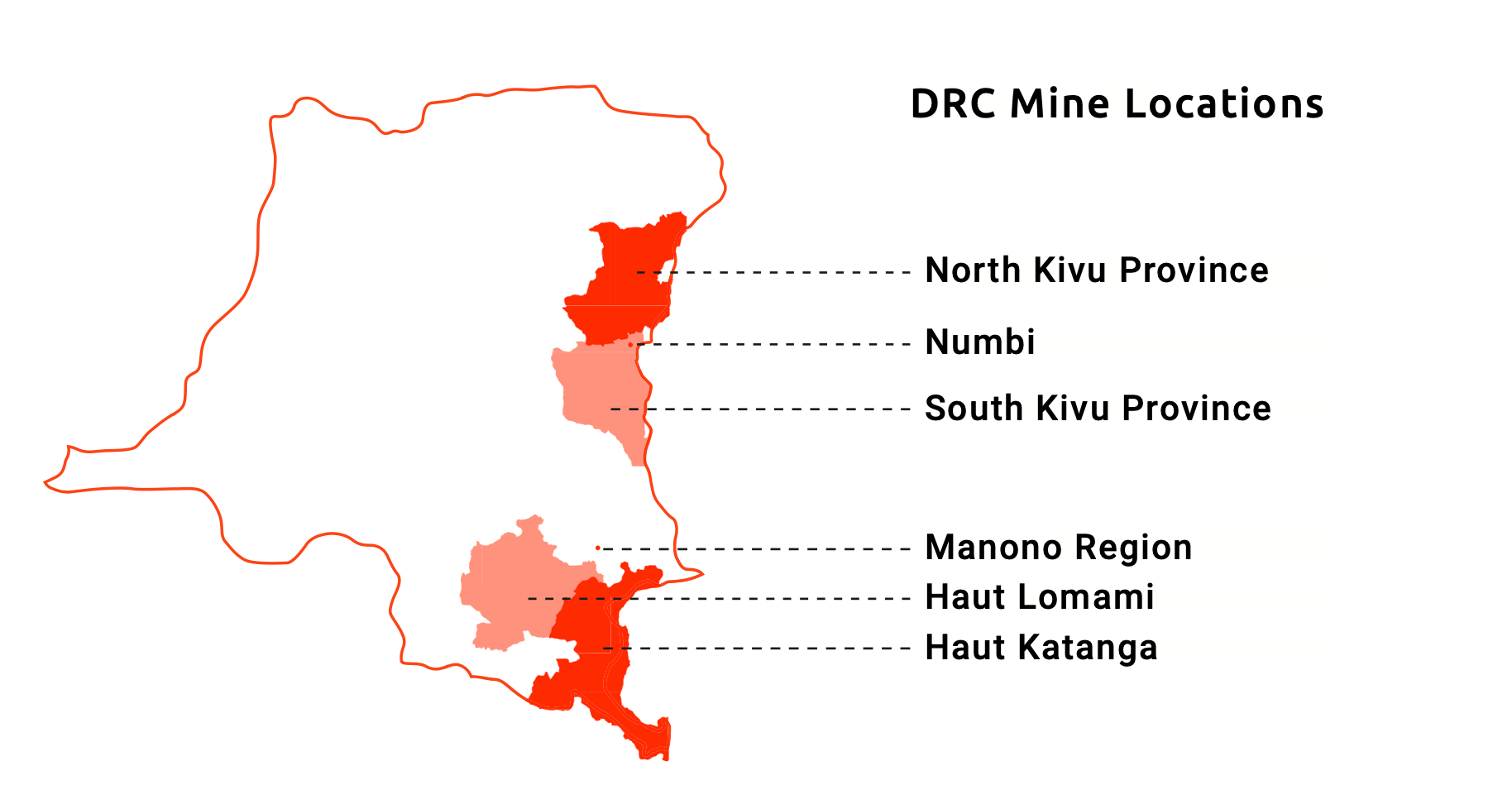

- Red flag identification: Monitoring for political exposure (PEPs), ties to high-risk industries like arms, mining, or energy, and links to already-sanctioned individuals or entities.

- Ownership and control checks: Mapping beneficial ownership and control structures can expose hidden ties. A company may not be sanctioned, but if it is majority-owned by a sanctioned individual, it still carries risk.

- Adverse media and OSINT: Local-language news, investigative reporting, and open-source data often surface issues years before regulators act.

- Network analysis: Studying business partners, subsidiaries, and joint ventures shows indirect exposure that lists do not capture.

Pre-sanction screening is not a prediction tool — it does not guarantee who will be sanctioned. But it builds a picture of likelihood. It helps organizations avoid entering relationships that could collapse if sanctions arrive, and it gives time to exit high-risk ties on their own terms rather than under regulatory pressure.

Why it matters

Sanctions lists are a baseline, not a safeguard. They tell you who is officially blocked, but not who is risky. Strong due diligence means combining official checks with investigative research, monitoring, and context.

Adding pre-sanction screening makes compliance proactive instead of reactive — lowering exposure, protecting reputation, and keeping organizations a step ahead of sudden regulatory shifts.