Tracing Copper’s Human Risks: A Zambia Case Study

The copper wiring and components powering our modern world carry a hidden human cost.

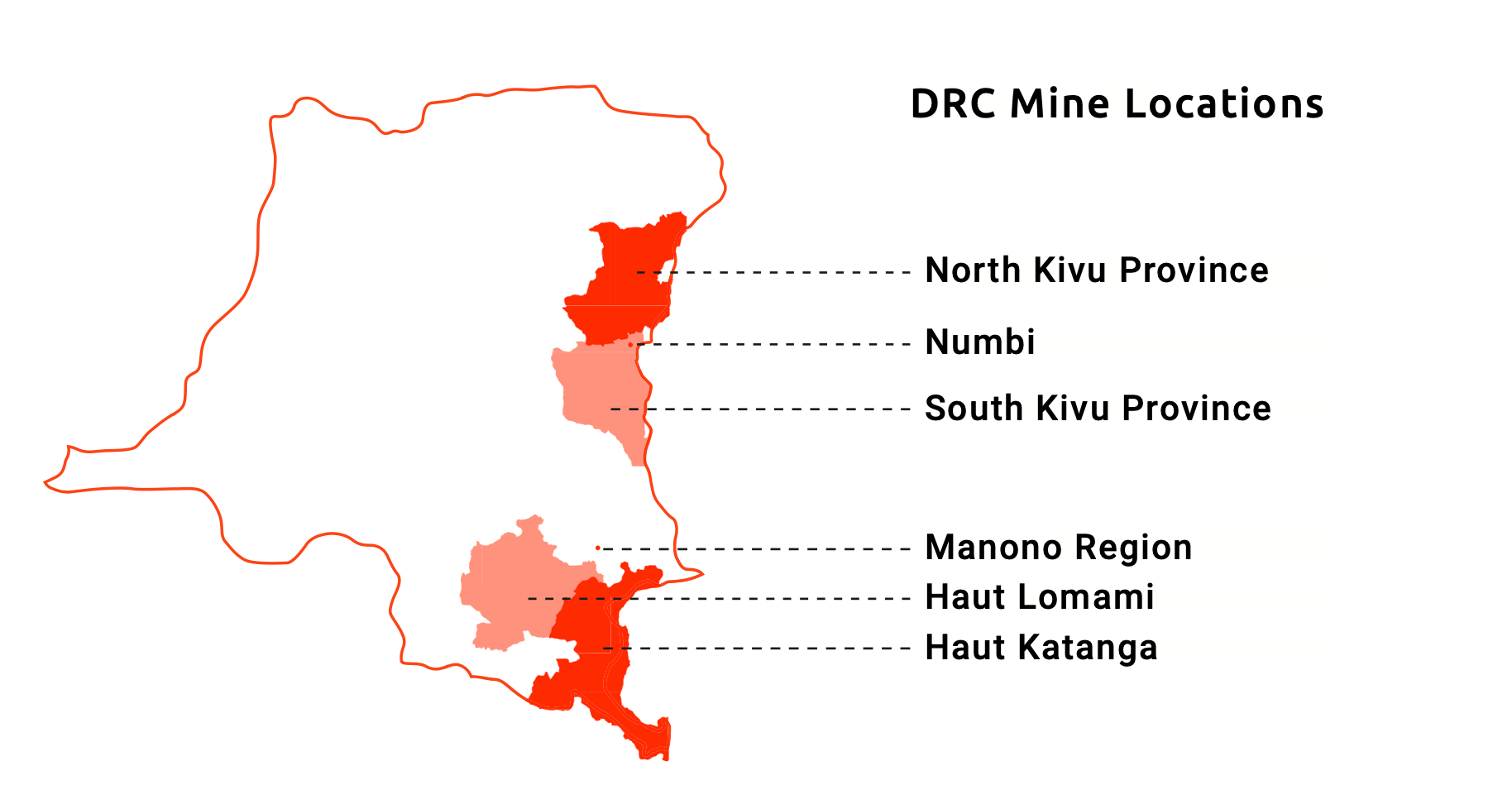

From the mines of Zambia and the DRC to processing plants in China’s Xinjiang region and even the locked-down mining sites of North Korea, vulnerable workers – including children – have been exploited at various stages of copper production.

A Global Metal with a Human Cost

Copper is ubiquitous in electrical infrastructure, electronics, construction, and renewable energy technologies. Global demand for copper is booming, especially with the rise of electric vehicles and clean energy, since copper is crucial for power transmission and batteries. Major producing countries include Chile - the world’s top producer - the DRC, Peru, China, and Zambia.

In the DRC, which sits atop the resource-rich Copperbelt, artisanal mines rely on child labor on a shocking scale.

A 2013 report found that 40% of artisanal miners in southern DRC’s copper and cobalt belt were children, some as young as eight years old working in hand-dug mine shafts.

Firsthand accounts described kids spending their days hauling heavy sacks of copper ore and even suffering serious injuries and illness from the harsh conditions. The U.S. Department of Labor officially recognizes copper mining in the DRC as being tainted by child labor – a grave violation of human rights and international labor standards.

Even in China, the world’s largest copper consumer and a major refiner, concerns have emerged about forced labor. In the Xinjiang region, where the Chinese government has instituted oppressive labor transfer programs targeting Uyghur and other Muslim minorities, a prominent copper mining and processing company was recently implicated.

In 2024, the U.S. government banned imports from Zijin Mining’s Xinjiang subsidiary (Habahe Ashele Copper Co.) over evidence it was profiting from forced Uyghur labor.

This move placed the firm on the U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act entity list, reflecting widening scrutiny of possible forced labor in Chinese mining operations.

At the extreme end of the spectrum lies North Korea, where the state itself compels labor in mines. The secretive regime’s export industry has long been underpinned by prison camp labor.

Investigations by the UN and human rights groups found that political prisoners in North Korea are forced to work in copper mines under brutal conditions. In one case, men imprisoned at Camp 12 (Jonggo-ri) were made to toil in a copper mine, with the “intensity and duration” of this involuntary work described as deadly.

North Korea’s use of forced labor in mining – including copper, coal, and other minerals – is institutionalized slavery, helping the regime earn hard currency.

By contrast, Chile’s large-scale copper mines – which supply over a quarter of the world’s copper – operate in a more regulated environment with established labor unions and oversight.

There are no reports of systemic forced or child labor in Chile’s formal copper sector, illustrating how strong governance can curb egregious abuses.

From Pit to Cathode: How Forced Labor Creeps In

To understand where labor exploitation occurs, it’s important to grasp the copper mining and refining process – and pinpoint its vulnerable points.

Copper typically begins its journey in open-pit or underground mines, where raw ore containing copper is extracted.

In industrialized mines such as the vast Nchanga open-pit mine in Zambia’s Copperbelt, heavy machinery and a formal workforce are the norm.

However, in many African and Asian copper sites, especially artisanal or small-scale mines, the extraction stage is labor-intensive and poorly regulated. While industrial mines are highly mechanized, artisanal and small-scale mining of copper often involves manual labor in unsafe conditions.

After ore is extracted, it must be processed and refined. The ore is crushed and milled to produce a concentrated form of copper minerals, which is then smelted at high temperatures to yield impure copper.

Finally, refined copper cathodes are produced via electrolysis. The smelting and refining stages are typically capital-intensive and thus dominated by larger companies – but they present their own labor risks.

For example, Human Rights Watch documented Zambian smelter and mine workers being pressed into 18-hour shifts with little regard for safety. There is also evidence from Indonesia and China of migrant industrial workers kept in factories under conditions that meet the criteria of forced labor.

Critically, once copper ores from various sources reach a smelter, they are combined and melted together, obliterating separate origin traces. This is why the ore-to-smelter juncture is a major vulnerability for traceability.

In regions like Zambia and DRC, artisanal miners – including children – dig copper ore by hand and sell it to middlemen. These middlemen might be agents of larger smelters or simply traders who aggregate ore.

Where criminal syndicates or corrupt officials are involved, coercion can enter the picture. The U.S. State Department reports that in Zambia some children have been forced by gangs to carry and load copper ore in mining areas. This amounts to forced child labor intertwined with criminal trafficking.

Case Study: Labor Abuses in Zambia’s Copperbelt

Zambia is Africa’s second-largest copper producer and has long been seen as a stable mining jurisdiction.

One major issue has been the conduct of foreign-run mining companies.

In the 2000s, as copper prices boomed, Chinese state-owned firms acquired several Zambian copper mines. By 2011, Human Rights Watch research revealed persistent labor abuses in Zambia’s Chinese-owned mines.

Zambian miners described 12-hour shifts deep underground without proper ventilation, lack of safety equipment, and threats of firing if they refused dangerous tasks.

One miner told investigators, “They just consider production, not safety. If someone dies, he can be replaced tomorrow. And if you report the problem, you’ll lose your job.”

The “jerabos” - gangs of copper thieves and illegal miners - also wield power in Zambia. They commonly invade old waste dumps or closed shafts to dig out copper ore remnants. Their operations are risky, but the economic lure draws in many locals, including youths.

Crucially, these gangs do not operate in isolation: illegal miners often sell to licensed copper buyers and traders, including some who double as influential crime kingpins. In fact, some crime bosses have obtained legitimate mining licenses or partnerships as a front, blurring legal lines. This integration means stolen or informally mined copper finds its way into the formal market with alarming ease.

Reports indicate that children are caught up in this underworld. Some youths scavenge ore from waste piles to earn a pittance. Others are exploited by gang leaders who force them to haul and load copper ore under threat. The U.S. State Department noted cases of children as young as 10 being compelled by jerabo gangs to carry copper ore to trucks in Zambia.

Zambia’s case shows a dual challenge: holding large companies accountable so that mines run by multinationals uphold labor standards and tackling the informal, illegal segment where forced and child labor thrive out of sight. Both require vigilant oversight and transparency in the supply chain.